Maskwitches is set somewhere around 8,000 years ago, give or take.

The people who lived there are very likely to have been part of a genetic group we now refer to as the Western Hunter Gatherers, or Western European Hunter Gatherers.

The available evidence shows that they had dark skin and blue or green eyes.

We have good evidence that this group of people later died out. Incoming waves of migration to this part of the world meant that this particular strand of humanity disappeared, their DNA scattering into more distant relations.

This means that as far as we currently know, the Western European Hunter Gatherers are not the direct ancestors of the people who currently live in the areas that remain above sea level bordering Doggerland/The North Sea. We’re all part of the greater human family, but it seems that no one alive today is directly related to those people.

This provides some fascinating things to think about around identity and geography. And I intend to spill a vast sea of digital ink meandering around this topic. Join me!

The first people who lived where I live were dark-skinned. I’m pale-skinned. I’m descended from a different genetic group, who migrated into this area much later. Every single person living here now is a migrant of some kind.

We, as modern people, obsess about the topic of so-called “race”, which we define in no small part by skin colour. It is apparently culturally important to us where I live in the broad “West”.

Attitudes towards this topic are frequently divided based on where you live in the world. So it is worthy of mention that I live in Scotland, and that my viewpoint is wholly based on my life and experiences here in Britain. People living elsewhere will understand these topics in different ways.

When you study the deep past, this topic of “race” can become entirely baffling, and that resulting confusion is something that I find extremely engaging. The relatively recent concept of “race” has a history, which can be studied and understood. That in itself is significant and is why I put “race” in inverted commas.

It’s worth noting I am aware that this topic is one that people are rightly nervous about. It’s extremely contentious.

People have not always thought the way we do now, and the modern concept of “race” is not a given, or “natural”, and there are reasons why we possess our current cultural norms. While it is not the topic of this piece, think of me pointing at the despicable practice of the transatlantic slave trade most of all when I talk about the contemporary idea of “race”. As an idea it is in no small part an economic construction. It’s certainly extremely difficult to unpick unconsidered attitudes to race from economics and material concerns.

I should also be open that my interest in this stuff speaks very much of a privileged position. I acknowledge that I am at liberty to find this stuff fascinating and engaging in an academic sense because I’m not being routinely judged on my skin colour.

If I were, I can at least imagine that I might not find the topic some curious thing to read and think about. And here we are at the first of the excruciatingly difficult topics.

While I do not have any qualification to write a game about being a person of colour, and while Maskwitches in no way sets out to be that, it does have some things to say about being. Curiously, the area the people in Maskwitches lived is geographically very close to where I live. “Race” and geography are apparently strongly intertwined concepts, so this untangling and retangling provides some food for thought.

I think a great deal about why I find it interesting and significant that the earliest people in this region of the world were dark-skinned.

I’m cautious around my engagement in the topic. The topic throws up questions for us living now which I think are engaging and worthy of thought, while remaining aware of my own identity in examining this topic, and my own qualification to examine it.

The ancestral connections to the Western Hunter Gatherers are so distant that we, meaning “everyone in the world right now”, are only related to that group in the sense that we’re all human. That’s wild. And throws up ideas of ownership of ancestors, identity and geography. The Western Hunter Gatherers don’t “belong” to any one group as direct forebears or cultural antecedents. That’s fascinating, and points to so many questions.

And for the people of what we now call Doggerland in particular their geographic homeland is entirely gone.

This provides an enormous amount to consider about place and identity, should we chose to engage with it. How people come to consider themselves “native” to a place. Or original or indigenous. These terms become extremely relative as we increase the timespans we are considering.

These are incredibly sensitive topics, which have been shockingly abused in more than one direction. Whether it is to privilege one group as being the original inhabitants of a place, or to demean them for the same reason as “primitive” or “precursor” people. Or elsewhere to point to the history of human migration and use that as justification for conquest and colonialism. “They moved here, so did we”. “We didn’t move here, they did”. Humans are very good at making in and out groups.

I’m intrigued by how the people who lived in Mesolithic Doggerland don’t easily fit into that dynamic.

My amateurism and arriviste status as a scholar of these topics is thrust painfully to the fore when I think about this subject. There’s just so much to learn about… everything. I’ve taken the liberty of including a reading list of books I’ve found helpful at the end of this article. I wouldn’t want anyone to think I am preaching a conclusion so much as I am querying which way is up.

—————

Fast foward 8,000 years

There’s a curious thing in how deeply some people living in Britain can connect themselves to the idea of an “unbroken” ancestry, deeply linked to geography, and find it significant to their own identity. While as reasonable people we might do well reject the “blood and soil” claims of diabolical mid-twentieth century extremists, elements of linking personhood and geography persist.

Let’s take, for example, the idea some of us in the UK and indeed the US, recognise the idea of being culturally or ethnically “Celtic”.

(Disclaimer: I am in no way criticising anyone who feels a connection to an ancestral past, or key cultural ideas connected to geography. “Celtic” peoples have been and continue to be victims of abuse and colonisation in the modern world. I’m using it as an example because I’m close to it, and a part of it.)

This is complicated by the fact that in everyday use, people use so many different meanings when they use the word “Celtic”.

But increasingly it seems that through the study of history and genetics, “Celtic” is more a set of ideas than it is a “genetic identity”. This annoys some people deeply.

Whether they are part of a group that identifies as “Celtic” or are in some way defining themselves as outside that group, there appears to be a desire for a deep connection to the past and geography that is physically within the self, and mere ideas just won’t do. There exists a desire for something much more tangible and permanent, and blood readily becomes a symbol for that permanence. The idea that we pass on our “blood” and that blood somehow contains culture, and thereby renders it permanent.

Which becomes a curious notion when we study the migratory nature of “the Celts” as both a people and a set of ideas.

There’s a mix of memes, geography and genes involved in how those ideas came to the region most commonly thought of as “Celtic”, and how they have been preserved. And again, when we study these things, commonly-held ideas we see around us start to dissolve. The facts that can be studied don’t always contain all the truths held about identity.

What does it mean, that for a just a short handful of centuries, during what we call the Iron Age, a group of ideas which we cluster together as meaningful, spread across Europe, some of which became later romanticised, codified, solidified, and used to define groups of people living in certain places to this day? Do we even understand the shorthand?

The people living in those places continue to share a name, with qualities attached to it shifting across centuries. What links Vercingetorix the Gaulish leader who defied the Romans in 52 BCE to Robert Burns the 18th Century Scottish poet? Both are considered “Celtic” people, both are avatars of the qualities of that group. And yet they’re so wildly divided by time and material conditions.

Some of the historic cultures which people use to define themselves are incredibly short-lived and sometimes extremely difficult to define in any concrete way. Or else rely on 19th century definitions long since abandoned by any serious scholar of these topics. See “The Vikings” as a prime example.

Yet we see the ensuing identities can be “felt” very strongly. They’re enacted in behaviours and symbols, and new symbols and behaviours are invented to further reinforce these imagined old identities. While clearly these do not reside in literal blood, it would be a fool’s errand to attempt to deny their significance to those who enact them and pass them on.

It’s not real but it defines us

It follows therefore that identity is something we both feel and create. It has factors that come from within, and those that are imposed from without. If a person in the first century BCE that we might call “a Celt” never met “a Roman” would they feel “Celtic”? Or would that identity only become visible and viable in opposition to a different group, which had different cultural ideas? Do we identify ourselves in opposition to others? Do we actually need others unlike ourselves in order to have a sense of identity? This is an interesting idea when we consider a people and place almost entirely lost to time.

As an immigrant to the place I currently live this engages me, and is readily visible all around me. While I only moved across a notional border from England to Scotland some 20 years ago, and thought little of it at the time, I found myself in a completely different culture with different second, third and fourth languages, Scots, Scots Gaelic, and Doric, of which I shamefully knew nothing, and people whose common experiences I unexpectedly did not share.

The rituals and language which I once unwittingly used to be part of the in-group now marked me as part of the out-group. I found that I didn’t understand commonly-used words. This expression of identity was genuinely shocking to me. I had become a stranger.

I find all of this stuff lights up my brain, and connects the study of the deep past with the present.

And more to the point with Maskwitches, speaks to one reason why thinking about these people who lived “here” before “us” is worthwhile.

Painting People

None of which is why I started writing this piece. That initial motivation to write is far more prosaic and sharply defined.

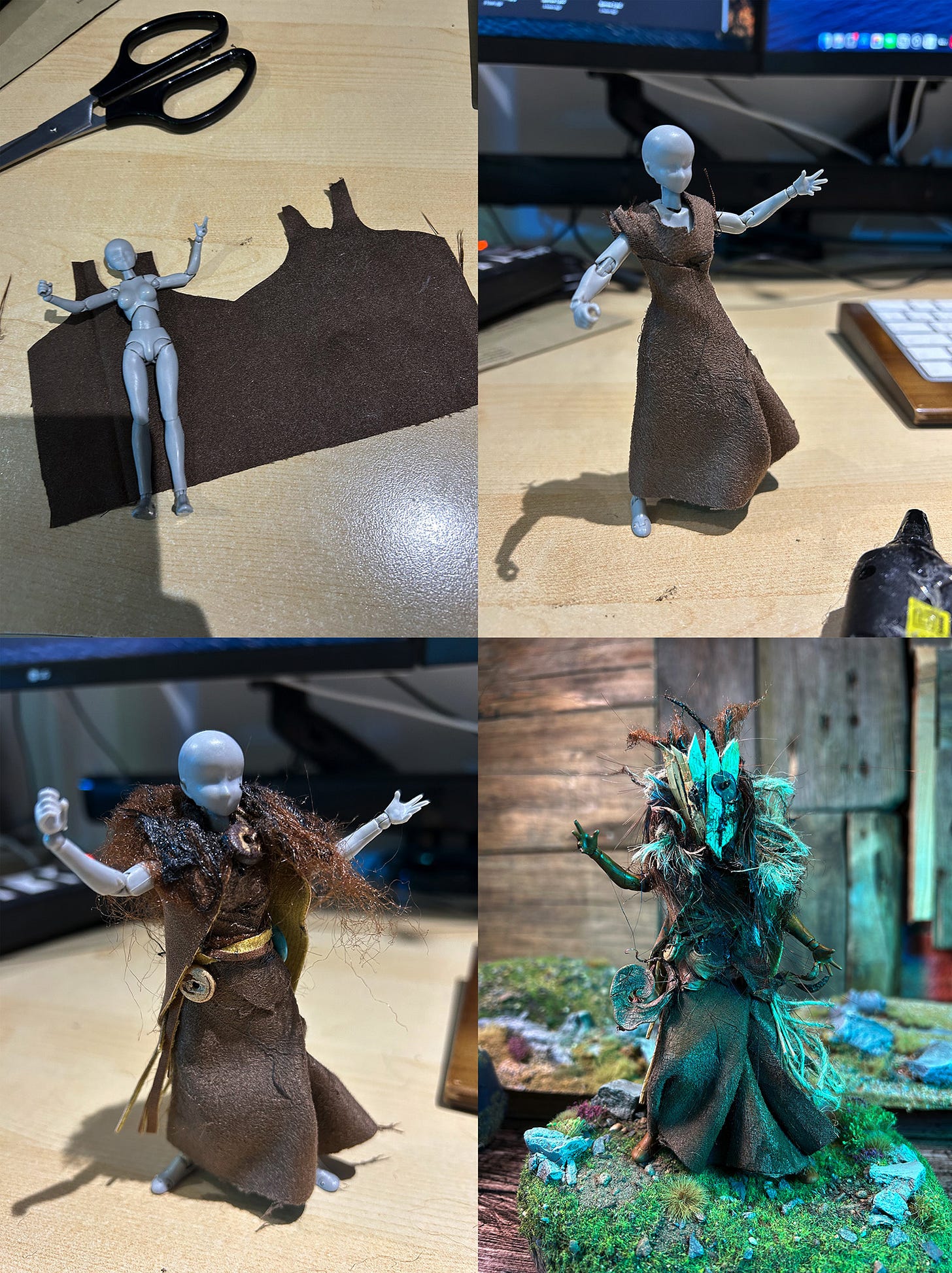

For Maskwitches, I needed some models of people to appear in my sets. Looking around my workspace, right at the beginning, I saw a little articulated plastic mannequin which is meant as a reference tool for artists. It was a good size to use for this project. I duly experimented with it, making some clothes, and shooting some test photographs. It all worked.

But the figure was a pale grey. The people I am depicting are dark-skinned. Which meant painting the figure. It felt a bit odd to do it, but on a grey plastic model painting on a human skin colour is less of a big deal. The grey is the colour of the plastic, and typifies a kind of neutrality. For those of us invested in making, grey is an undercoat or a primer. It’s a state of readiness.

Then I got some more figures. These weren’t grey. They were a pinkish colour, clearly meant to invoke the skin tones of white people. That isn’t nearly as straight forward is it? I’m painting these models to be a different skin colour. That’s got some troubling echoes. That’s uncomfortable.

Now, being practical about it, these are plastic models. They’re not people. I’m not sure that a plastic mannequin can really perform black face.

I’m also fairly certain that in the wider scheme of things, representing these now-extinct people whose genetic make-up clearly has something to say about modern topics is, in short, a good thing. I don’t want to shy away from the fact these people, these first truly human inhabitants of north west Europe, were dark-skinned. I absolutely do not want to erase, evade or reduce that factual matter. No matter how upsetting it appears to be to some folks who apparently crave whiteness above all else.

I’m intrigued by the reactions I’ve received from those who want to diminish it as a matter of historical fact. The Wikipedia page detailing this topic, which so many “common sense” experts draw on when discussing it, can be a deeply unstable battleground of opposed political ideas.

But painting these pink models brown gives me pause. The physical act of doing it was remarkable. Having contextualised it in this essay means I now regret not documenting the process. At the time it felt like crossing a mighty threshold and I feared it as I did it. I didn’t stop to take photographs.

Thinking

It strikes me that there’s an angle I could take, and which people have suggested to me, of simply saying “it doesn’t matter. Don’t worry about it”.

That’s not really how my art works. It does matter. I do think about it. I try to think really hard about as much of it as I can. That’s the point. Thinking about it is where the work comes from. The experience mattered, and that’s why I’m talking about it, and in doing so presenting a certain kind of vulnerability.

(Credit: Michael Lipsey - https://www.tumblr.com/stoicmike)

I’m also aware that one “fix” for this discomfort would be to find some mannequins that were manufactured to be dark-skinned. The fact that’s not easy to do is extremely relevant. The fact the default is grey plastic or pale pink is relevant. The fact I have to transform these models by painting them to better represent the people of ancient Doggerland is significant and is now a part of the work. This essay is a part of the work.

(Picture credit: Raymond Pettibon)

The gone people

Maskwitches of Forgotten Doggerland is in part about identity. The idea that people lived “here” long ago, and they’re now gone, that an actual sea now occupies the place they lived. A more literal demonstration of them being gone would be hard to think of.

There’s something romantic and tragic about lost family of people who lived here long ago, who were the first “us”, but who might not be the same as “us”. That really makes us think about what “us” actually means. It might change the way we look at us, and our relationship to time and to place.

To some, the colour of those people’s skin will be more significant or even shocking than to others. Some will seek to equivocate or diminish it. To try to somehow make the first European humans not “of Africa”, because they feel it destabilises something about their own identity. For others it is just an unfolding an interesting fact, and something to consider and from which to draw meaning. Perhaps others will find it heartening, and capable in some small way of undermining some old harm. None of that is up to me, but I can point at a thing.

Unknowable

The unknowable nature of those people of Doggerland very much informed the idea of the Maskwitches having a deeply unstable identity as people, and as an organisation.

The capabilities of the Maskwitches you play in the game are defined moment to moment by the masks they wear. The nature of the Maskwitches as an organisation or tradition is determined by each group in play. Nothing is permanent, and identity is constructed by contingency.

There’s something about “being” in all these things. About symbols and culture and meaning. Painting a plastic person a different colour and finding it a highly significant and even troubling act isn’t unrelated to the matter of Maskwitches and their shifting identities.

It’s curious to think of some people mentally repainting those people to suit their own ideas, desires or needs: of masking them to better fit a contemporary circumstance.

The Maskwitches project continues to present wheels within wheels and reflexive kinds of meaning. It’s been and continues to be a very strange journey.

You can now sign up to be notified of the campaign launch to print the new edition of Maskwitches. Sign up here.

Useful Reading

The History of White People, Nell Irvine Painter

African and Caribbean People in Britain, Hakim Adi

Ancestral Journeys, Jean Manco

Black and British, David Olusoga

Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire, Akala

Thank you for this.